PBA President Patrick Lynch, joined by relatives of slain officers Tuesday, urges state lawmakers to change how the Parole Board decides who is released. (Reuven Blau / New York Daily News)

The city’s largest police union wants convicted cop killers to stay behind bars forever.

The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association urged the state Parole Board on Tuesday to reverse how it assesses cases, making the nature of the crime the top factor in determining if a prisoner should be freed.

The PBA, along with two widows of officers killed on the job, also urged state lawmakers, during an emotional news conference at the labor organization’s office in lower Manhattan, to codify how the board operates.

PBA President Patrick Lynch and other law enforcement leaders are furious the board released convicted cop killer Herman Bell in April after a nearly 40-year prison stint.

Lynch told reporters that he believes in redemption but not for people like Bottom and other convicted cop killers.

“We are not talking about a mistake by a young person,” Lynch said. “What we are talking about is evil that can’t change.”

In 2016, Gov. Cuomo announced that the board would use a new risk assessment system to determine if a prisoner should be released. The Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions system incorporates “an inmate’s current score on a risk and needs assessment.”

The system also directs the board to consider the “diminished culpability” of the prisoner based on their age at the time of the crime. Prisoners are also judged on how they have behaved behind bars.

On Tuesday, relatives of two officers killed decades ago joined Lynch to slam the system.

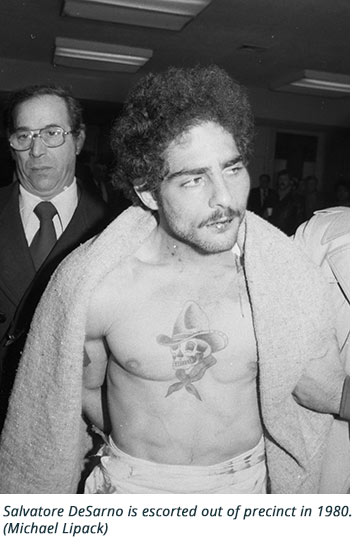

“It is difficult for me to even imagine how any right-thinking person could consider for a second letting Sal DeSarno back onto our streets where he will most certainly return to a life of crime and violence,” said Linda Sledge, whose husband, Cecil Sledge, was killed by DeSarno on Jan. 28, 1980.

During the fatal encounter, DeSarno was out on parole for an unrelated armed robbery. Sledge pulled him over in Canarsie, Brooklyn, to write him a traffic summons.

During the fatal encounter, DeSarno was out on parole for an unrelated armed robbery. Sledge pulled him over in Canarsie, Brooklyn, to write him a traffic summons.

But DeSarno, worried he would be hauled back into prison because he should never have been driving, shot at Sledge, 35, who then got caught on the car’s bumper. The cop’s body was dragged for a quarter mile until DeSarno smashed into a house.

“Had he committed this crime today, he would have been given life without parole, which is the only appropriate sentence absent a death penalty,” said Linda Sledge, who had a 3½-year-old son and 9-month-old daughter at the time.

Police widows view their husbands' names on PBA Memorial Wall on Tuesday. (courtesy of the Patrolmen's Benevolent Association)

Mary Beth Ruotolo-O’Neil also urged state lawmakers to revamp the parole board.

Her husband, Thomas Ruotolo, was fatally shot by George Agosto, who was on parole for manslaughter, in 1984. Ruotolo, 30, was responding to a radio call of a stolen moped when he spotted Agosto, 24 at the time, at a gas station.

Agosto opened fire at Ruotolo and his partner, Tanya Brathwaite, who was wounded in the back.

“This was not his first kill,” Ruotolo-O’Neil said. “He murdered my husband while out on parole.”

The Parole Board has also come under harsh criticism from prisoner advocates who argue all board hearings should be done in person. The board has begun to use remote videoconferences to handle the hundreds of cases that come up each year.

In a rare display of unity with prisoner advocates, Lynch said that he also believes the board should meet prisoners, and victims, in person before making decisions.

The Cuomo administration pointed out that a sentence can’t be adjusted after it has been handed down.

“The Governor proposed determinate sentencing two years ago but that effort was rejected by the legislature,” said Cuomo spokesman Tyrone Stevens. “We of course remain open to considering any further amendments to the law that are constitutional and advance public safety.”