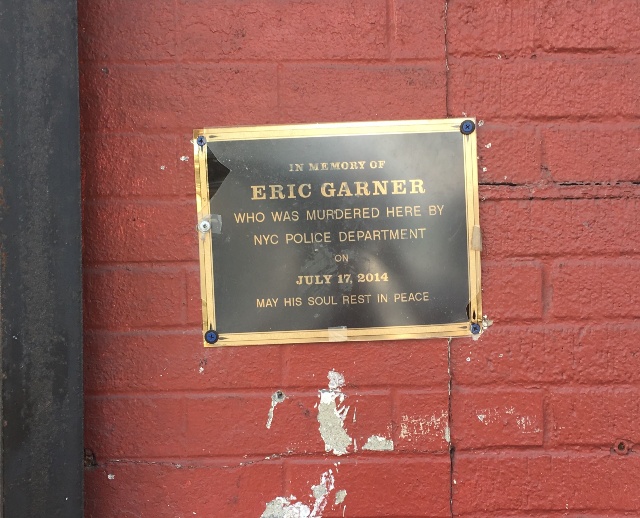

A makeshift plaque marks the spot where Eric Garner was brought to the ground by Officer Daniel Pantaleo." Or "A T-shirt vendor on Bay Street in Staten Island, named Doug, posted a makeshift plaque in the spot where Eric Garner was brought to the ground by Officer Daniel Pantaleo. (Yasmeen Khan / Gothamist / WNYC)

A makeshift plaque marks the spot where Eric Garner was brought to the ground by Officer Daniel Pantaleo." Or "A T-shirt vendor on Bay Street in Staten Island, named Doug, posted a makeshift plaque in the spot where Eric Garner was brought to the ground by Officer Daniel Pantaleo. (Yasmeen Khan / Gothamist / WNYC)

With the disciplinary trial for New York City police officer Daniel Pantaleo winding down, the decision on how to discipline Pantaleo, if at all, will rest with Police Commissioner James O’Neill. The trial judge, Deputy Commissioner Rosemarie Maldonado, will make a recommendation, but O’Neill has sole discretion over the matter.

“Miss, I’m not paying attention to no trial because I already know the outcome,” said Trevon Murden, when I approached him on Bay Street on a recent afternoon in the Tompkinsville neighborhood of Staten Island. “They’re going to say he was performing his duty.”

Tae Hillman, who works for a non-profit in the neighborhood, said she had indeed been following coverage of the trial. Though she was just as skeptical as Murden about the outcome.

“It’s disgusting to see no justice at all,” she said. “You’re literally going to lose your job — possibly — and go find another one probably doing something similar.”

The most severe punishment that Pantaleo could face for using an apparent chokehold against Garner — a banned maneuver because it is deadly — is getting fired and losing his pension. A Staten Island grand jury declined to charge Pantaleo criminally; a federal investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice has yet to reach a resolution (and the statute of limitations on federal charges is quickly approaching).

Nearly five years after Garner’s death, it is easy to find deep-seated anger around what people view as unchecked police power.

“They still look at you as [though] you’re black first, instead of being a human being,” said a man named Doug, who asked that his last name not be used.

Doug is a fixture on Bay Street, selling T-shirts, incense and other things on the same portion of sidewalk where Garner was brought to the ground by Pantaleo while being arrested. In the video just before Garner died, he denied that a crime was even taking place.

Doug noted that he’s 68 years old, and feels that little has changed in his own experience being surveilled by police.

“Who the hell do these people think they are?” he said. “I just get pissed off every time I think about it. Why you focusing on me? All these people walking up and down the street, why the hell you focusing on me? That’s all my fucking life.”

There are some changes in the 120th precinct, at least on paper. Police stops have declined dramatically here, as they have all over the city. In 2014, police recorded nearly 2,000 stops. In 2018, that number was just over 120.

Arrests, however, remained steady at about 4,500 for 2018, even while arrests declined citywide over the last five years. Arrests for misdemeanors dropped slightly.

And the quality of interactions between community members and police remain another issue entirely.

“It’s sad when you live in a community and you’re in fear of the police in your community,” said a man who goes by Jah Dreddz.

He’s a father of four; his children ranging in age from 16 to 21. He says he’s had negative interactions with officers, as have his kids. But he singled out his neighborhood officer as a positive example.

“I have a cop, her name is Mary,” Dreddz said. “She doesn’t come there and abuse her authority. She talks to you. She lets you know maybe where you made a wrong move. She’s not quick to just slap handcuffs on you.”

He is speaking of Officer Mary Gillespie, assigned to Richmond Terrace Houses, about one mile from Bay Street. She is a neighborhood coordination officer, part of the NYPD’s neighborhood policing initiative launched in 2015.

“It’s never easy coming into a community where the tensions are high,” Gillespie said in a phone interview.

She’s been a cop for eight years, and in her current assignment since 2015. She said she started building relationships with small gestures such as friendly “hellos” and filling kids’ bike tires. Over time, these interactions deepen, she said.

“They get to know about my life, I get to know about theirs,” Gillespie said. “You know, when you think about it, I spend more time with the people of this community than I do with my own family. And that’s why it’s important for me to have a strong relationship with them.”

And that’s the intention of the neighborhood policing program. In fact, it was created in part in response to the protests over Garner’s death in 2014 and other Black Lives Matter demonstrations that followed.

“The NYPD — we deal with protest all the time, but this was different,” Commissioner O’Neill said in an interview with WNYC late last year. “This was protest against us.”

O’Neill said the demonstrations made it clear that something needed to change.

“We had to make sure that our police officers had the training and the opportunity to make connections to the people that they’re sworn to protect and serve,” he said. “It might sound a little corny, but it’s not.”

While there might be positive developments with neighborhood policing, or other NYPD divisions where officers work hard to build relationships with residents, people still want accountability when things go wrong.

In 2014, shortly after Garner’s death, the Daily News reported that officers in the 120th precinct had the highest number of civil lawsuits against them. The Legal Aid Society’s CAPstat database tracks federal lawsuits on police misconduct in New York City and shows that the 120th precinct still ranks in the top ten in the city, according to lawsuits filed from 2015 to June 2018.

Hillman, the young woman who works for a non-profit in the Tompkinsville neighborhood, said it’s impossible to build trust overall when there appear to be few consequences for police misconduct, or even police mistakes. Especially when there is a life lost.

She said the lack of accountability for Garner’s death sends a message to the people the NYPD is supposed to protect and serve.

“Just another black man dead,” she said. “That’s how I feel.”