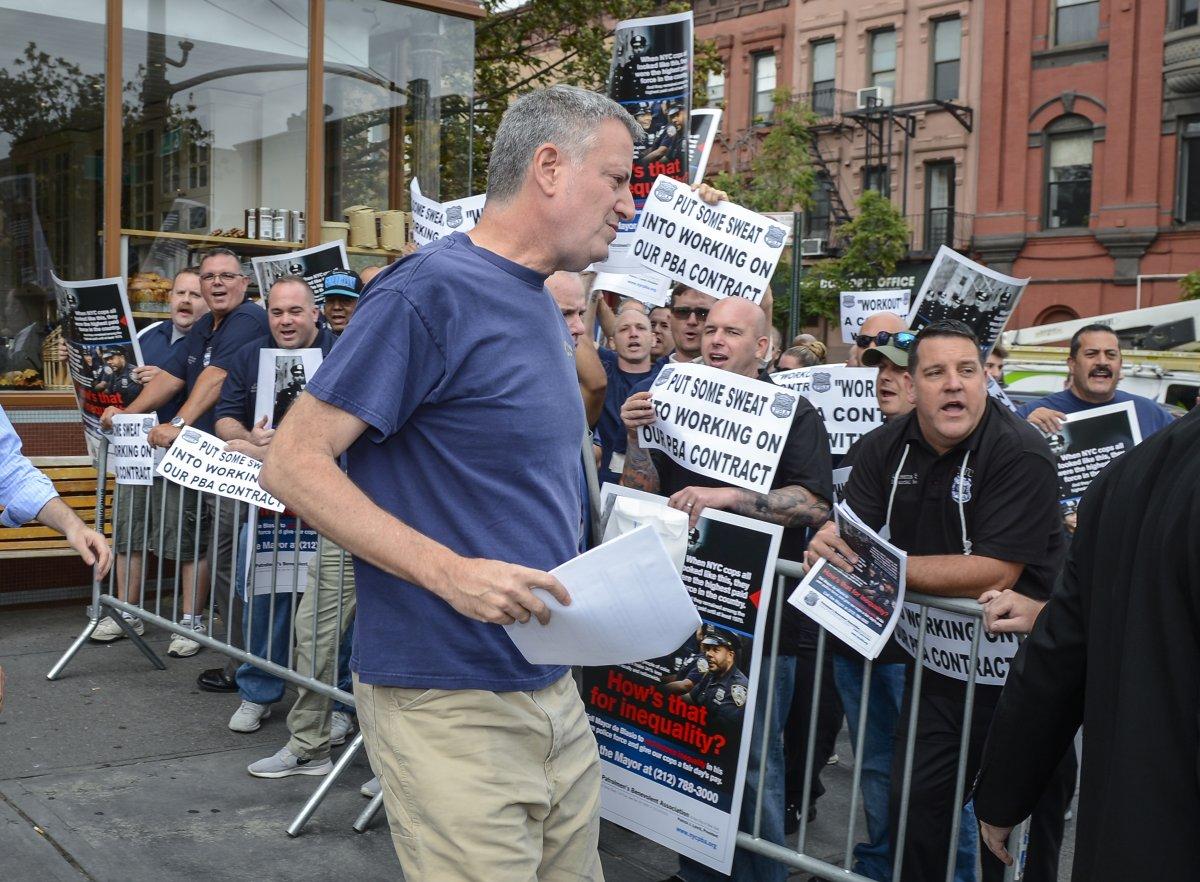

Give cops what they’re owed (ANTHONY DELMUNDO/NEW YORK DAILY NEWS)

"New York City is a union town!”

That was Mayor de Blasio’s proclamation to members of the electrical workers union — IBEW Local 3 — a few months back, during a solidarity rally supporting their strike against Spectrum Cable and its parent company, Charter Communications.

The mayor praised the strikers for “fighting for something we all should care about — the right to have a good pension, the right to have decent pay and decent benefits.” He called on Charter to step forward to negotiate with the union in good faith “or suffer the consequences.”

Since then, some 1,800 members of Local 3 have remained on the picket lines; their families continue to suffer. At more than eight months and counting, it is now New York City’s longest strike in three decades.

Yet the promised “consequences” for Charter have not been forthcoming from City Hall.

Will the newly reelected mayor ever follow through on his promise to support Local 3 and protect New York’s “union town” reputation? For that answer, Local 3 members should look to the experience of the unions that know him best: those representing the employees who work for him.

Local 3 might be surprised to learn that de Blasio recently offered New York City police officers 31/2 years of absolutely zero raises unless we agree to the same kind of retirement and health care cuts demanded by Charter.

They also might be shocked to discover that de Blasio has granted city workers the smallest raises that we have seen in almost 50 years. Even Mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg offered a minimum of 13% and 17.15% raises, respectively, for the first seven years of contracts they negotiated. De Blasio only offered a baseline of 10%, which is further diminished by dramatic health care givebacks.

Unfortunately, Local 3’s situation is a textbook example of the double bind faced by working women and men across the country:

On the one side, union members face a well-honed management strategy that asks them to pay for their own raises by sacrificing their retirements, their health care, their time off, and even their work-rule protections. Those who accept this deal are quick to discover that their raises have been eaten up by the rising cost of living, while the rights and benefits they traded away are gone for good.

Those who resist may seek support from traditional labor allies in government, where they’ll receive plenty of encouraging words but often very little in the way of action.

Meanwhile, those same pro-labor elected officials are using the anti-worker management game plan against their own employees — claiming they believe the deck is stacked against working people. Then, they turn around and use that same stacked deck to deal themselves a favorable hand.

All of this serves as a clear sign that — in a “union town” like New York — we are not doing enough to hold our elected leaders accountable for their labor records.

This year’s mayoral race was Exhibit A. The assumption that labor would remain united behind the mayor, among other factors, kept the most viable challengers on the sidelines. There were decent, honorable candidates who remained in the race, but from the outset they had no clear path to victory.

Many voters who were dissatisfied with the mayor’s labor policies — or any of his other policies, for that matter — saw no point in casting a protest vote and instead stayed home. He continued to portray himself as a friend of labor throughout his campaign, knowing full well that working New Yorkers had little leverage at the ballot box.

While the mayor is no longer stumping for New Yorkers’ votes, his future ambitions surely depend on maintaining his worker-friendly image. He should be forced to earn it.

The mayor may claim, with some justification, that there is a limit to the influence he can exert over a private-sector labor dispute. But if he is going to stand up before union members and promise “consequences” for a callous employer who won’t come to the table, then he needs to deliver them.

And in the one area of labor relations over which he has complete control, he needs to stop behaving like one of the “greedy corporations” he rails against. Only then can he say that New York is a union town.